“Gas War” between Russia and Ukraine in the Geopolitical Context

Recently, the future of Russian gas transit through Ukraine has grown into one of the hottest and most contentious geopolitical issues. Problems that always existed between Ukraine and Russia in the gas sector have become particularly acute after annexation of Crimea and armed aggression in Donbas and have by now evolved into a fully fledged “gas war”.

Pipeline gas supply from RAO Gazprom is the single most important source of natural gas for Europe, almost equal to the EU indigenous production. In 2015-2017, Gazprom enjoyed three years of growing sales to Europe. According to some estimates, its exports to Europe, including EU-28 and reverse gas sales to Ukraine, accounted for more than 180 bcm in 2017. Without Ukraine, the figure stands at 167 bcm(28% growth since 2015). According to Gazprom’s own estimates, its share of the European market had increased from 27% in 2011 to 35% in 2017. Most experts agree that Gazprom is likely to further strengthen its position in the European energy market.

Potential growth of demand for gas in Europe creates a number of serious questions for policy makers, among them: availability of Gazprom’s production capacity, possible infrastructure constraints and potential use of monopolistic market position as a tool for political manipulation. The experts estimate that Gazprom may have up to 80 bcm of spare production capacity if required. In the longer term, the company has huge reserves that could support growth in demand. It is, therefore, rather safe to assume that in the near future any constraint on Russian gas exports to Europe will not be caused by shortage of production but rather by the gas transit capacity. This fact brings armed conflict in Ukraine and the “gas war” with Russia as one of the most important energy security issues into the Europe’s geopolitical context.

What are the Interests of the Parties Involved?

Russia’s objectives in the “gas war” with Ukraine are the following: 1) to demonstrate that Ukraine is the weakest link in the supply infrastructure and thus create better political acceptance for alternative transit routes such as Nord Stream-2 (NS-2); 2) to keep Ukraine’s transit route as a spare (standby) capacity; 3) to maintain, if possible, certain levels of gas supplies to Ukraine’s domestic market.

In the wake of the armed conflict in Donbas, Russia (Gazprom)has formally adopted a strategy to bypass Ukraine via two alternative transportation routes: north and south of Ukraine (NS-2 and South Stream, which was subsequently cancelled and later revived as TurkStream).

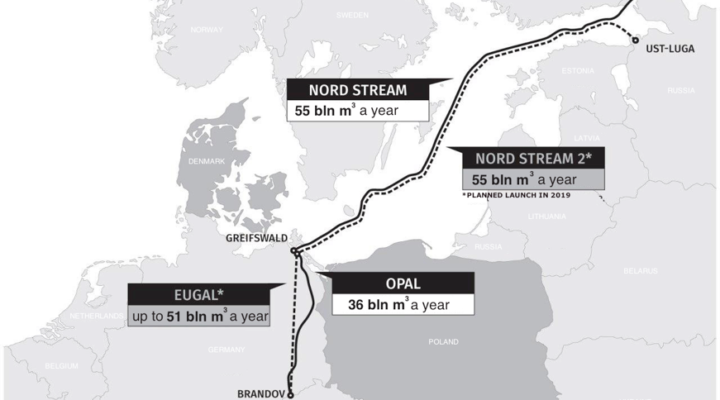

The planned NS-2 pipeline runs about 1,225 km through the Baltic Sea from the Ust-Luga in Russian Narva Bay to a German city of Lubmin on the Bay of Greifsvald and has a projected cost of Euro 9.5 billion ($11.7 billion). The pipeline system comprises two parallel pipeline strands 1.2m in diameter each and a combined transport capacity of about 55 bcm per year. By end-2017, NS-2 consortium (Gazprom, ENGIE, OMV, Shell, Uniper, Wintershall) already signed Euro 4.5 billion worth of contracts with 670 companies from 25 countries. Over 70% of pipes (of 200,000 needed) have already been produced and now at storage yards at various locations, with 1/3 ready for pipe lay. With technological capacity of more than 5 km/day, the project, when launched, is expected be completed in over 300 days, i.e. by end 2019.

The NS-2 requires various government approvals from 4 countries (Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Finland), of which only Germany has already provided them. Key decision rests now with Denmark because only in this country the undersea pipe is to pass through sovereign territorial waters. In Sweden and Finland, where approvals could be expected without any significant delays, pipeline is to run through their exclusive economic zone regulated by the UN law. Denmark, after joining so called “Skripal Coalition” of 14 EU members and with adoption of the law allowing the government to ban the project due to national security reasons, has become so far the biggest uncertainty risk to the NS-2.

Ukraine’s Interests. The country’s political oligarchy that traditionally controlled the domestic gas distribution and transit business has always straddled the fence in the act to balance the interests of two geopolitical players, EU and Russia. The 2014 conflict with Russia has tipped the balance clearly in the EU favour but vested interests and in-fighting have stalled implementation of genuine energy sector reforms. For Ukraine, the key question should not so much be whether Naftogaz continues to ship Russian gas after 2020 at all BUT how much of its transit capacity is going to be contracted.

EU Interests. Being dependent on Russia’s energy supplies, several important EU members are interested in reducing risks of gas transit through Ukraine mainly by encouraging the country to pass clear, predicable and corruption-free rules of the game. Even through EU members have somewhat diverging views on Ukraine transit, a clear position of the European Commission is that Europe’s energy security lies in diversification of supply and transit and, therefore, in Ukraine maintaining its role as a transit route. It is most likely that the EC will continue its present strategy not so much to prevent this project as to limit its utilization by amending the Gas Directive as well as by trying to broker with Gazprom a guarantee for a certain volume of future transit for Ukraine.

What is the Recent Gas Transit Situation?

Ukraine has been the main route for transiting Russian gas to the EU since early 1990s. Transportation of gas to Europe is based on the 2009 transit contract with Gazprom, which expires on December 31, 2019. In the last 7 years, Ukraine’s actual transit volumes (bcm), according to Naftogaz, dropped from 104.2 bcm in 2011 to 62.2 in 2014 and subsequently increased to 93.5 bcm in 2017.

How did Stockholm Arbitration Rulings Affect Russia-Ukraine Energy Relations?

The Stockholm arbitration rulings, contrary to the EU earlier expectations, have established neither any basis for reconciliation in the gas relations between Russia and Ukraine nor created any reliable foundation to improve them in the future. On the contrary, the rulings led to further escalation of tensions. Gazprom refused to pay $2.56 billion to Naftogaz as well as to supply gas to Ukraine, while Ukrainian courts arrested Gazprom’s assets in the country as well as threatened to start seizing Gazprom’s international assets.

The bilateral talks between two state monopolists, mainly on the future of gas transit through Ukraine, are taking place against the background of protracted armed conflict in Donbas, further deterioration in relations between Russia and the West as well as against the background of much more intensive lobbying campaign pro and conthe NS-2 pipeline. The fact that Ukraine joined “Skripal Coalition” as well as the latest US sanctions against Putin’s close circle of oligarchs added additional pressure and “spice” to the ongoing “gas war”. At the same time, Gazprom, despite continuous offers from the EU, refuses to broaden the format of bilateral talks.

End of Part 1.

Yuri Poluneev